Excerpt from Clay Bodies

“Death is only an old door set in a garden wall.”

— Nancy Byrd Turner

I scan three evenly-spaced hooks on the hall mirror that collect the household keys.

We almost drove off without it: the key to the Garden of Memory, without which we would be wasting a trip.

It’s been at least a decade since we last made the hour-long drive to Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, long enough that I’d forgotten what the key looked like. My younger self must have predicted this, folded the blue, red, and yellow child’s name sticker on its head, connected it to a Marvelous Mom keyring, knowing this day might come.

I text Mom a picture: “Found it!”

My husband Lloyd backs us carefully out of the driveway, Mom and I riding in the second row chatting and directing our “chauffeur.”

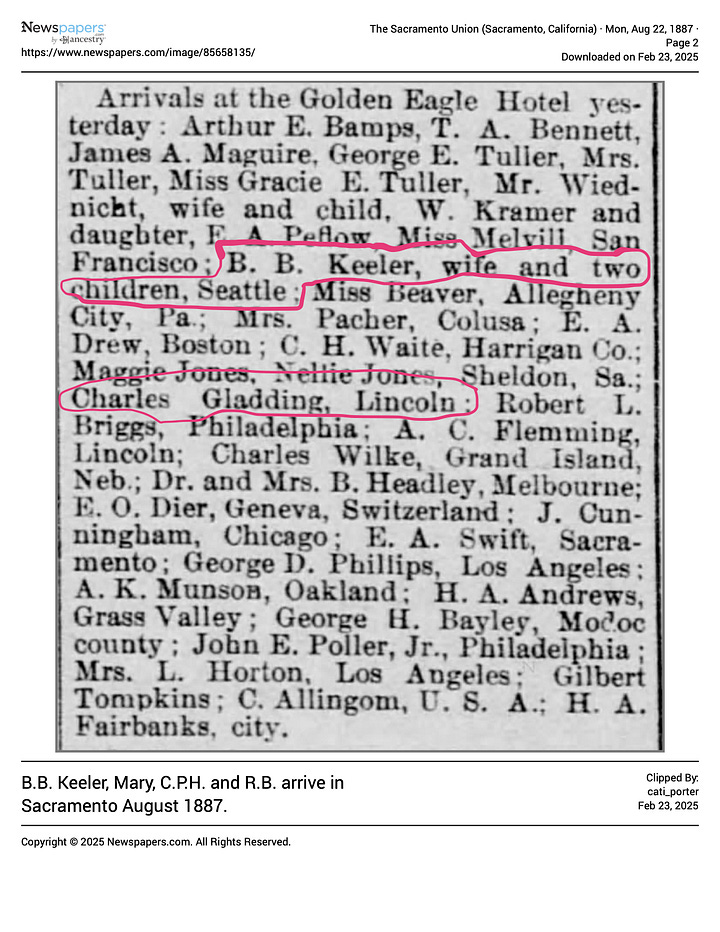

Forest Lawn was the site of regular family picnics in Mom’s childhood. It’s where her father, Brad, is buried, behind an impenetrable locked door in that “garden of memory.” Great-Grandma Mary, Great-Grandpa Rufus, Uncle Bud, and Great-Great-Grandfather Burr all share a tiny vault in the Great Mausoleum, like the entire family squeezed into an efficiency apartment.

When Mom’s dad died, her older brother, Brad Jr., was just sixteen, and middle child Pat was ten. Mom, the baby, was only four. After Brad’s death, the family would take a picnic and lay out blankets around the little lake with the heron fountain, right near the main entrance. As Brad Jr. and Pat married and their families grew, the smallest kids would entertain themselves by chasing the swans and ducks. Uncle Brad had a home movie camera that he wielded mercilessly. In one series of frames, Mom leans toward a big white duck with an open palm, then looks up with a broad smile to wave at her older brother behind the camera, Mom already recognizable as Mom. Nearby, one of Mom’s cousins—which one? Shari? Or Christie?—steps back from an aggressively approaching swan. It’s a series of jump cuts then, first to the Gardens of Memory, then to the various other statuary around the perimeter, then back down to ground level, zooming in on Grandpa Brad’s headstone, and finally on to the Court of David, lingering on the stark white marble figure.

These are some of her happiest memories, she says.

When we were here last, my Bradley, Grandpa Brad’s namesake, played leapfrog over the grave markers and refused to sit for a picture. Both sons, now young adults, had exactly zero interest in joining us today. Maybe in another decade we can try again, but by then Mom will be 83 and I will be 60, and who knows if the world will even still exist. But every generation thinks that, hallmark of getting old. Now that I’ve turned the corner on fifty, I’ve outlived the ages of both Grandpa Brad, 39, and Great Grandpa Rufus, 49.

The closer I get to my expiration date, the more alive the dead feel to me.

Lloyd makes a right, then another right, and now we’re on Cathedral Dr., passing through the impressive wrought iron gates and past the pond and the storybook tudor and brick mortuary, the Little Church of the Flowers, following the circuitous route to find The Court of David, our landmark.

In the courtyard, we are just children, Mom and I, giggling about the Statue of David’s gigantic penis. We pose beneath him for a photograph: me in my denim skirt and straw hat, and she in her striped thrift-store palazzo pants and brocade bag.

David stands on a pedestal in the courtyard in the Center of a star—elbow crooked, hand to his chin, lost in thought. He doesn’t seem as tall as I had remembered him, and something else seems off. I pull up the photo app on my phone, scroll to find our photos from eleven years ago. And there he is—huge, stark naked, marble-white.

Why is he green now?

David’s courtyard is walled, each segment inset with a bas-relief sculpture and tablet inscribed with a corresponding story: David and Goliath, Michelangelo’s Studio, the 23d Psalm. There is an opening to our right, a path to follow. We take it and enter The Garden of the Mystery of Life.

With his hands folded behind his back, Lloyd’s head is lowered, reading the ground-level tablet explicating a sculpture depicting eighteen figures at different ages and stations, all peering down at the Mystic Stream of Life. The inscription invites viewers to see themselves among the figures, asks the question, Gentle reader, what is your interpretation? I don’t relate to any of them, except maybe the slow turtle on the bank that the small boy on hands and knees is closely examining. The mother of boys, I can imagine him, on a whim, picking up the turtle and throwing it across the courtyard.

*

A brief detour into the world of Forest Lawn.

Forest Lawn was created by a guy named Dr. Hubert L. Eaton in 1917, who had the brilliant idea to combine a park-like setting with a cemetery, because who wouldn’t want to lunch in close proximity to the dead?

Within the Courtyard of the Garden of the Mystery of Life, there is a set of weathered copper double doors. Grandpa Brad is the odd man out, the only member of our family buried in the ground at Forest Lawn.

A turn of the key and we are in.

To our right is ‘America’s Sweetheart,’ Mary Pickford, in a family crypt decorated with cherubim and fruit. There are other famous people here too, though we don’t know where.

The grassy expanse is long and wide as a football field, punctuated by row upon row of grave stones like a series of dashes. Some have clever quotes and laser-etched photographs. Not Grandpa Brad’s. His is plain, with only his name, years of birth and death (1913 and 1952, respectively) and the phrase Beloved husband and father.

Mom, fingers laced, stands beside the stone, flip flops flattening the grass. We pose here for a photograph: two generations above ground, one below.

We linger until she’s ready to leave, which is longer than I’d planned but shorter than she’d stay if she could. Lloyd has gravitated to the other end of the lawn, looking back as if herding us toward the exit.

We turn to go, because we still have another stop.

To “see” the rest of the family requires driving to the Great Mausoleum, which is in fact great and even a little bit spooky: immense and impressive as a castle, but not in the cloying Cinderella castle way; more like terrible Castle Bran in Romania, with arches and spires and made entirely of steel-reinforced concrete. Why they call this place the “Disneyland of graveyards” is beyond me.

Double doors from the parking lot open onto a cavernous interior cool as a cave. A security guard is seated in a booth behind glass. I address her.

“Hi, we don’t know where we’re going.”

The guard gives me this look like, don’t you waste my time. Lloyd gives me a cringey look the equivalent of a face palm but I keep going.

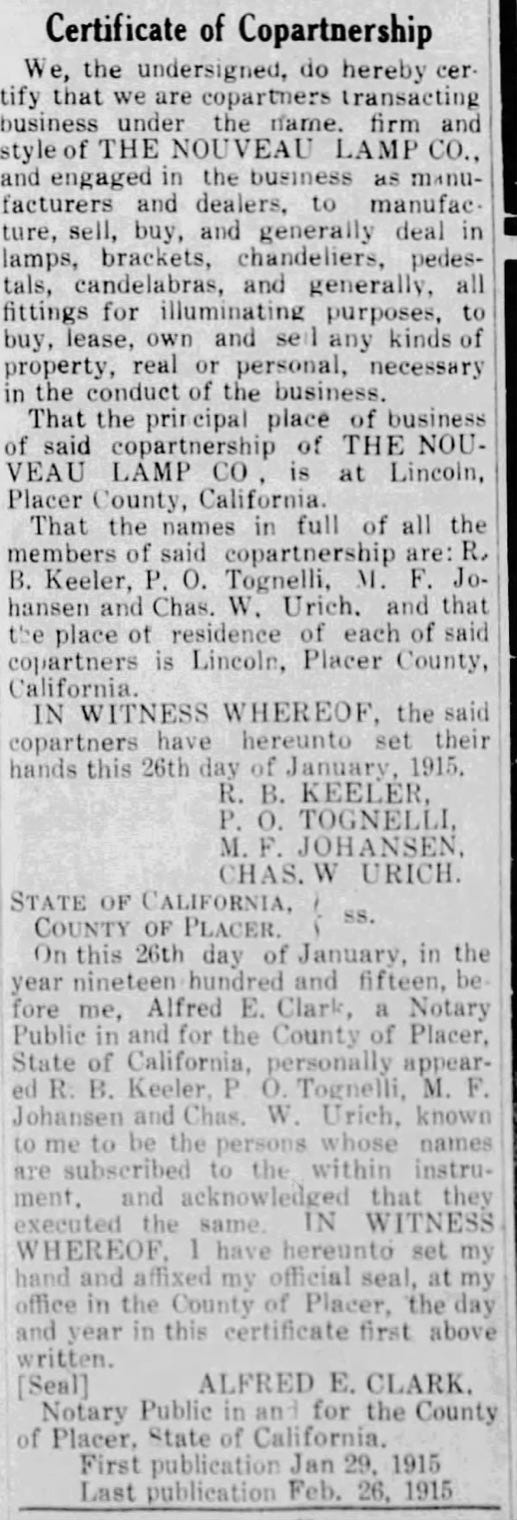

“Our family is interred here. Keeler. Rufus Bradley Keeler. Can you please tell us how to find him?” The guard’s fingers move across her keyboard. The screen lights up with the information we need. She jots down a number on a scrap of paper thrust in my direction, waves her arm as if to say, that way.

*

“I think I know how to get there,” Mom says, and we follow because what else is there to do but trust that she knows the way.

The halls are churchy, lined with antiquities–faux? The focal point is a backlit stained glass replica of “The Last Supper” which takes up the entirety of the far wall. Even to me, a non-believer, the faces of Jesus and his disciples are reverential. Then I spot a name recognizable to few except for those familiar with Riverside’s Mission Inn, or of a certain generation: Carrie Jacobs-Bond, songwriter, commemorated with a bronze plaque of a woman at the piano framed by stage curtains, a ribbon of music rising up. With her is the adult son who predeceased her, and briefly I consider the grief that accompanies outliving your child.

I look up to see that Mom and Lloyd have moved on without me.

At the foot of the entrance to Columbarium of the Sanctuaries, I pause to snap a picture of my feet with the inset stone marker. I want to memorialize this so that it will be easier to find next time.

The word columbarium comes from the Latin word for pigeon, columba, and quite literally means “pigeon house.” Our family’s pigeon house is just inside and to the left of the entrance, first column on the left, a few rows up from eye level. I make note of these coordinates. This wall, our wall, is within the “no public access” section of the mausoleum. There are ninety-four other family niches, most larger and more ornate, some even behind glass, visible but just out of reach.

I am reminded of the world of ways one can keep the dead.

Grandma Vi kept Grandpa John, my dad’s dad—really, his stepdad—in a styrofoam ice chest in the garden behind their mobile home, where she could sit with him outdoors.

Every niche here, in the Columbarium of the Sanctuaries, has a little bud vase. In spite of having a florist for a sister, I gave no thought to bringing flowers today.

There is a photo in the family album of a fluffy white pigeon perching calmly on my Grandma Catherine’s hand, its own wooden “pigeon house” just visible in the lower corner. Her face is out of the frame, but I know it is her–one arm outstretched, hand open, palm up, cupping its claws. Nothing is preventing the pigeon from lifting off.

There is an often-told family story of how, at the home in Glendale, a dog – whose? – managed to get a hold of one of their pigeons and tore open its breast. Calmly, Brad told Catherine to wait while he ran and got a needle and thread. Then he gently sewed it up. The bird lived. This must be the bird, all puffed up, dapper in his white feather coat.

One last stop before leaving Forest Lawn. Yes, a mausoleum museum and gift shop.

And here I find the answer to the why of the green David.

A white marble replica of David’s head lay on its side, eyes wide, pupils fixed, like the head of Holofernes. I read the plaque.

Created by Italian artist Oreste Andreini in 1937, this “original” replica—not even the one I remember from my last visit with Mom, but the one before it—was already brought down by the time I was born by the 1971 Sylmar earthquake. Over time, five more replicas would fall. After having learned their lesson, this last replica is cast in immutable bronze.

Nearby stands the severed marble stump of David’s foot.

Mom balances like a flamingo beside it, raises her right leg forward to compare her own size six flip-flop-clad foot. The top of the ankle comes to her waist–just the right height for her to steady herself, oblivious to the sign that says, “Please do not touch,”

I point the camera and shoot.

Catherine Porter

Catherine Porter